Australian scientists have described the evolution of immunity levels up to four months following COVID-19 infection, finding that while antibody levels drop dramatically in the first one to two months, the decrease then slows down substantially.

The findings suggest that protective COVID-19 vaccines should ideally generate stronger antibody responses than natural infection.

The research team, including University of Melbourne Dr Jennifer Juno, a Senior Research Fellow at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute), have been investigating how the immune system, particularly B and T cells, responds to the COVID-19 spike protein.

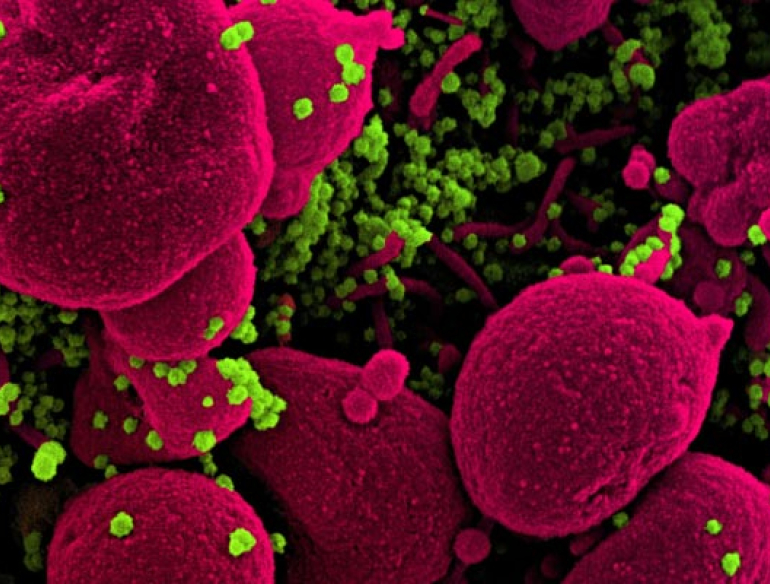

The spike protein enables SARS-CoV-2 to attach and enter cells in humans and is crucial in inducing neutralising antibodies to protect from re-infection.

B cells are responsible for producing the antibodies that recognise SARS-CoV-2, while T cells play an important role in supporting the development of the B cell response.

Dr Juno said one of their striking observations was that over the four months they were tracking the patients, the number of B cells recognising the spike protein actually increased in almost all of them, regardless how severe their disease was.

“This is interesting because our work and other recent studies suggest these B cells are continuing to accumulate and potentially evolve over time. That should be useful for protection in the event of another exposure in the sense that those ‘memory’ cells should be able to be activated again,” Dr Juno said.

“While we still don’t know how much antibody you actually need to be protected, either through a vaccine or through natural infections, the recent results from phase 3 vaccine trials should soon allow us to understand how long natural immunity should last.

“In addition, what remains to be understood is whether these changes in B cell memory can help the immune system to recognise and be protected against new SARS-CoV-2 variants that are currently emerging.”

Dr Juno said recent data on the leading vaccines show they are eliciting at least double the antibody levels as natural infection, which is very encouraging.

This research was conducted in collaboration with the Kirby Institute at University of New South Wales and Flinders University.

The Kirby Institute’s Infection Analytics Team was involved in the analysis and modelling of the experimental data coming from the University of Melbourne and Flinders labs. “We were interested in calculating the ‘half-life’ of different immune response as they declined after infection. We found that responses tend to decline more rapidly soon after infection, and then become more stable. We used these half-lives to develop a simulation to predict how long immunity might last under different assumptions,” said Professor Miles Davenport, program head for the Infection Analytics Program.

Written by the Doherty Institute.

Peer review: Nature Communications

Funding: NHMRC, MRFF, Victorian Government

This research used human samples.

Media Enquiries

Catherine Somerville, Senior Media and Communications Officer, Doherty Institute | +61 (0) 422 043 498, catherine.somerville@unimelb.edu.au