A major international clinical trial conducted by researchers at the Kirby Institute at UNSW Sydney in collaboration with global partners in the INSIGHT network has found that a treatment that was long assumed to improve the health of people with severe influenza infections, in fact, provides no clear clinical benefit. The results of the trial were published in The Lancet Respiratory and have revealed crucial gaps in our understanding of immunotherapies to treat influenza.

Why test this influenza treatment 100 years later?

The 1918 influenza pandemic killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide. In the absence of viral drugs, ‘plasma’ or blood collected from individuals who had recovered from influenza were given to patients with severe influenza-induced pneumonia. The thinking behind this early form of immunotherapy was that plasma from those who had recently recovered from influenza would be enriched with protective antibodies (also called immunoglobulins) to the circulating influenza strain. It was hoped that administering these high levels of anti-flu antibodies, or ‘convalescent plasma’ to severely ill patients might prevent their condition from deteriorating during the time it took for their own immune system to respond to the virus.

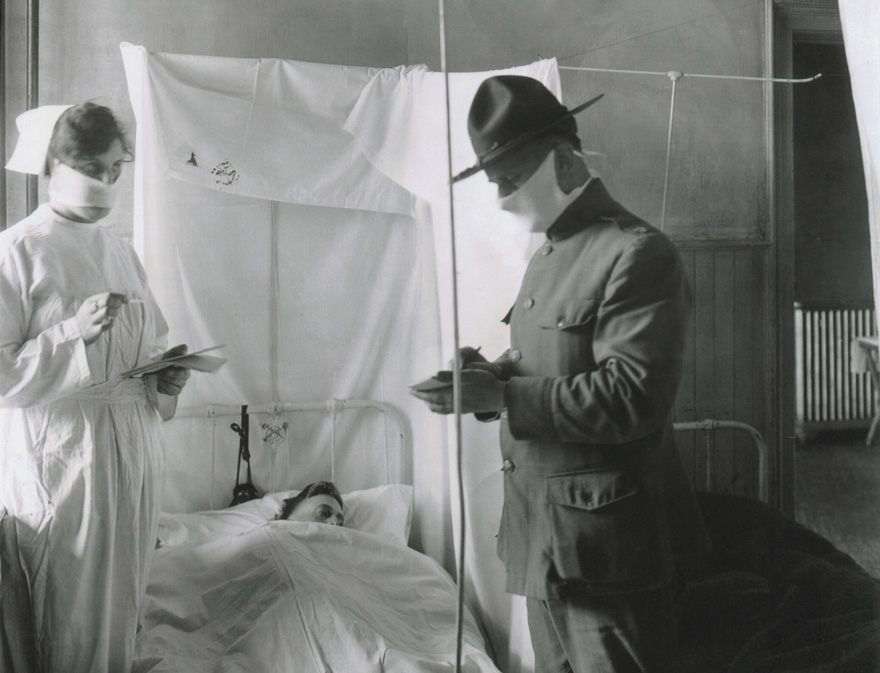

Spanish Influenza in American Army hospitals. Masks and cubicles were used at Fort Porter, where patients' beds are reversed, so breath of one will not be directed toward another. Nov. 19, 1918. Shutterstock.

Spanish Influenza in American Army hospitals. Masks and cubicles were used at Fort Porter, where patients' beds are reversed, so breath of one will not be directed toward another. Nov. 19, 1918. Shutterstock.

Since that time, several studies have shown beneficial effects of convalescent plasma. However, they were small, did not include careful comparison groups, and did not account for the improvements in supportive care and the availability of anti-viral medications over subsequent decades.

Until now, the theory that using antibodies (or immunoglobulins) from immune people to treat patients with severe influenza had not been properly tested.

A world-class team with clinical trials insight

To find out whether immune plasma could improve treatment outcomes in adults hospitalised with the flu, a group of international researchers collaborated through the global INSIGHT clinical trials network and designed the FLU-IVIG study. FLU-IVIG, was conducted in 45 hospitals in Argentina, Australia, Denmark, Greece, Mexico, Spain Thailand, UK and the USA. The Kirby Institute’s Therapeutic and Vaccine Research program was one of the four centres worldwide who coordinated sites participating in the trial.

The study enrolled 329 adults who had been admitted to hospital with either influenza A or influenza B infection. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either 500 mL of immune plasma, or 500 mL of saline solution as a placebo in addition to the normal standard-of-care treatment.

Dr Dianne Carey from the Kirby Institute was the clinical project coordinator for sites in Australia, Thailand, and Argentina. “Rolling out the FLU-IVIG trial was a mammoth organisational endeavour,” said Dianne. “We not only had to find patients with immune plasma, but we had to ensure that the plasma was available at the clinical trial sites during the height of the flu season, which is in a different month in each country.”

“We had the additional challenge of needing to keep the plasma below minus 25 degrees Centigrade at all times, and shipping from the US to sites in Argentina, Thailand and Australia was tricky as customs or quarantine delays could mean the plasma thawed and was unusable. This trial required high levels of precision and organisation from each of our collaborators, and it would not have been possible without their immense efforts.”

Dr Dianne Carey and Associate Professor Mark Polizzotto from our Therapeutic and Vaccine Research Program.

Dr Dianne Carey and Associate Professor Mark Polizzotto from our Therapeutic and Vaccine Research Program.

Surprising results

In an unexpected result, the study found influenza immunoglobulins did not provide a treatment benefit for patients infected with the most common form of flu, influenza A. However, a benefit was seen in patients infected with the less common form of flu, influenza B.

Associate Professor Mark Polizzotto, Head of the Therapeutic and Vaccine Research Program at the Kirby Institute was the lead Australian author on the paper. “For one hundred years, the theory that immunoglobulin therapy was effective in treating influenza had not been properly tested. Now this rigorous randomised trial has shown it does not improve outcomes for people with the most common form of influenza.”

A potential plan A for influenza B?

The immunoglobulin products used for the FLU-IVG study were selected based on their predicted value in fighting influenza A, but the trial enrolled patients with either A or B in order to build a stronger evidence-base in both forms of influenza.

“We predicted the benefits to be more apparent in patients with influenza A. Surprisingly, the effect was the other way around,” said Mark. “This unexpected result suggests that our current understanding of the way antibodies work against influenza A is not accurate, and that influenza B could differ from influenza A in quite a fundamental way that we don’t yet understand.”

“This is what is so exciting about a well-designed clinical trial,” said Mark. “While we didn’t prove our primary hypothesis, we identified a potential therapy for influenza B and uncovered important new scientific questions about how the immune system responds to this potentially deadly virus and new knowledge to inform our understanding of the variations in the flu virus.”

The INSIGHT FLU-IVIG trial was primarily funded by the NIAID Intramural Research Program and the NIAID Division of Clinical Research, NIH, and the legal sponsor for the trial was the University of Minnesota. This project has been funded in whole or in part with US federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. Support for the London and Copenhagen International Coordinating Centres was also provided by the UK Medical Research Council and the Danish National Research Foundation.

Contact

Luci Bamford, Media and Communications Manager, Kirby Institute

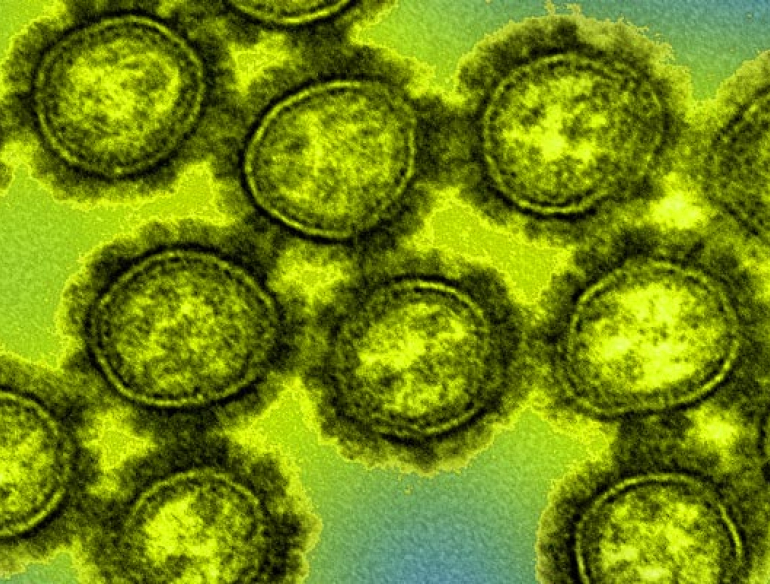

Header Image

Colorised transmission electron micrograph of H1N1 influenza virus particles by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).