New research from the Kirby Institute at UNSW Sydney, published today in PLOS Pathogens, combines a study in monkeys with mathematical modelling to reveal that the body’s immune defences can inhibit viral rebound from elements of the HIV latent reservoir; information which could provide a possible avenue for long-term HIV control.

HIV treatments suppress the virus in the body to undetectable levels, but one of the major barriers to curing HIV is this ‘latent reservoir’ of infected cells that initiate viral rebound whenever treatment is stopped.

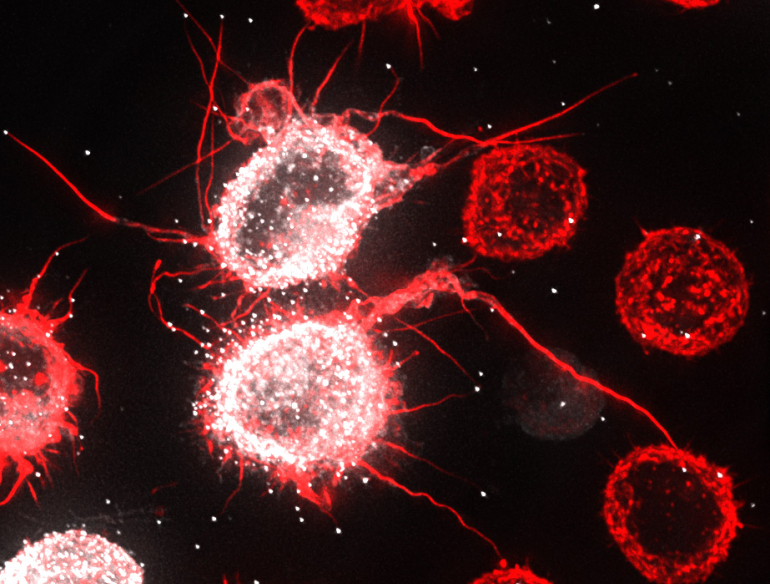

This occurs despite the fact that there are immune ‘killer’ cells, called CD8+ T cells, that can target cells infected with HIV.

“It was previously thought that killer cells are recruited too late after treatment is stopped to be effective at blocking rebound of the HIV virus,” explains Dr Steffen Docken, who is lead author on the paper. “Our research demonstrates for the first time that this is not the case, and in fact killer cells can inhibit rebound of a portion of the latent reservoir, which is more susceptible to killer cell pressure.”

The research used a unique ‘barcoded’ SIV virus (the monkey version of HIV), that allowed the scientists to observe the ‘waking up’ of latent cells following two separate treatment stoppages – one after 29 weeks and one after a total of 42 weeks of treatment. Analysis of virus from before versus after treatment revealed the effect of CD8+ T cells when treatment was stopped.

HIV is a highly complex and evasive virus. When it is active in the body, it is capable of mutating very quickly in such a way that it resists the killer cells that the body’s immune system produces. “What our research shows is that the killer cells are very good at attacking the original virus when it reactivates after treatment is stopped. But it is the virus that has ‘escaped’, or mutated, that remains a complex challenge.”

Understanding the HIV latent reservoir, and how to control the high diversity of viral mutants contained within, is thought to be the key to HIV cure research. While many questions remain about how to target HIV-infected cells as the virus quickly mutates, this research unlocks new information about the complex interactions between the virus and the body’s immune system.

“This research both confirms that CD8s play an important role in controlling HIV - and maybe could play a stronger role - and brings us closer to characterising which strains and mutations of the virus, lying dormant during antiretroviral treatment, can reawaken if treatment is stopped,” says Professor Miles Davenport, senior author on the paper. “While an HIV cure is still a way off, these little pieces of the puzzle bring us closer to that goal.”