Despite recent declines in HIV among gay and bisexual men, genetic analysis shows that most of Australia’s transmission still occurs among this group.

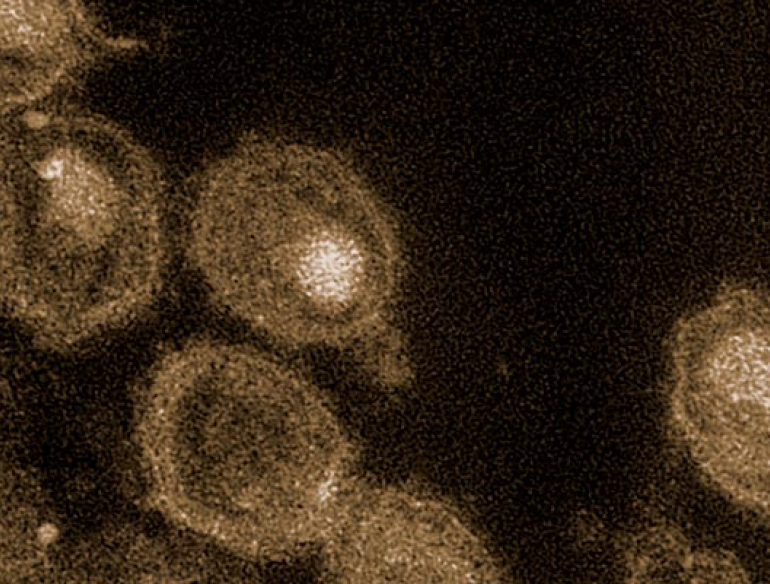

Like any virus, the movement of people from travel or migration helps HIV spread across the globe. We have seen this with the current COVID-19 pandemic in almost real time, where small transmission clusters in one part of the world can lead to larger epidemics elsewhere. Understanding how viral subtypes move through populations can provide critical information to inform prevention strategies.

To increase our understanding of the impact of HIV sub-types on HIV transmission in NSW, a team of researchers from the Kirby Institute have undertaken two innovative new studies. The research centred around the molecular genetic analysis of routinely collected HIV data. This type of analysis is called ‘molecular epidemiology’.

In order to understand the impact of these findings, it helps to understand variations in types of the virus. There are two types of HIV: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is by far the most common and infectious globally, including in Australia. But there are also subtypes, or strains, within each HIV type, with HIV-1 subtype B being the most common in Australia, Europe and North America – but in NSW, there has been a recent increase in diagnoses of non-B subtypes. The studies aimed to understand to what extent transmission clusters for subtype B contributed to new HIV diagnoses in NSW between 2004 and 2018.

“The two studies used HIV sequence data that is routinely collected as part of HIV testing,” explains Dr Francesca Di Giallonardo, who led the studies. “This sequence data indicates which subtype is present in a positive HIV test result. The information is de-identified, and we then retrospectively link it to demographic data from the HIV notification database via the Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL).”

The first study, published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society, found that the number of subtype B clusters is growing, and that a small number of clusters have also emerged in NSW in more recent years for one of the non-B subtypes. Infections among men who have sex with men and among individuals diagnosed during the first 12 months of infection were associated with these clusters.

The second study, published in Viruses, also found smaller numbers of clusters for non-B subtypes overall. It also identified numerous demographic differences between B and non-B subtypes. For example, a significant increase was observed for non-B infections among men who have sex with men and young adults not born in Australia.

“Molecular epidemiology helps us identify changes in transmission, providing us with insights that we can’t get from clinical data alone,” says Dr Di Giallonardo. “This information can reveal the missing puzzle pieces in transmission pathways, which is crucial because the more we understand about transmission, the better our HIV prevention strategies will be.”

Overall, the two studies confirmed the NSW notification data: that the majority of HIV transmissions in NSW were still occurring among men who have sex with men. It is important to note that the time period covered in this study does not yet show the effects that the listing of PrEP, the HIV prevention medication, on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme in 2018 has had on community transmission rates.

These studies were undertaken as part of a large NSW HIV Prevention Partnership Project which includes researchers, clinicians, the public health sector, and the HIV positive community. Dr Di Giallonardo says that the insights gained from the studies help achieve the Partnership Project’s aim of reducing HIV transmission in NSW. “Later this year we will undertake this analysis again, and include data from 2019 and 2020. From there, we hope to be able to quantify at molecular level the impact of the rapid uptake of PrEP among men who have sex with men on driving down HIV in NSW. These insights will strengthen the evidence base for the rollout out of similar programs in other settings.”